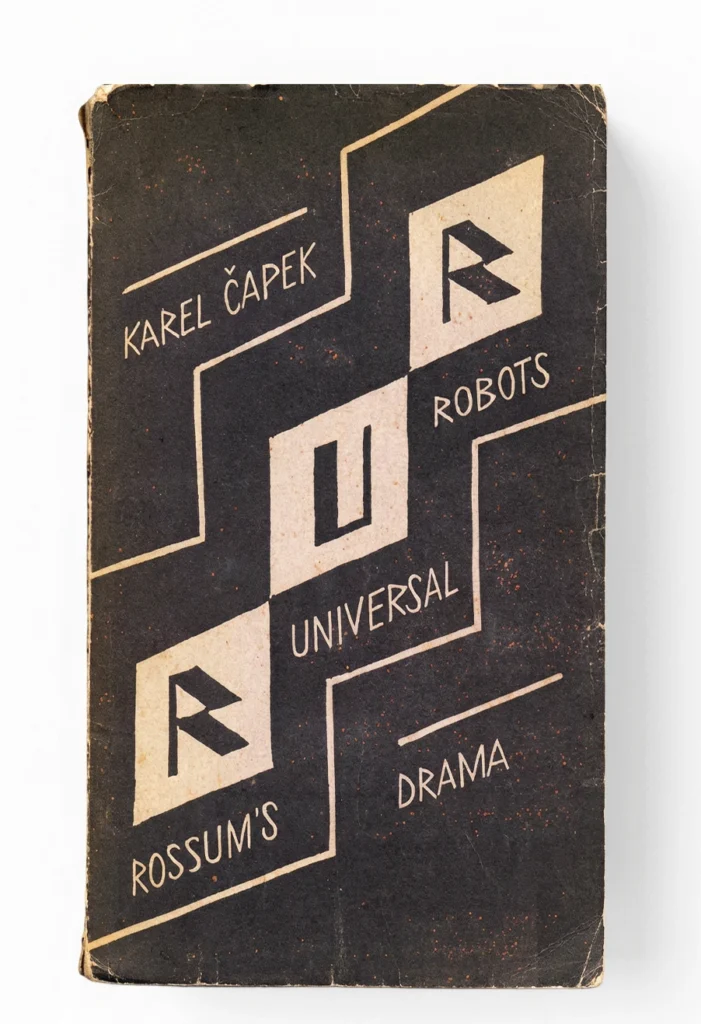

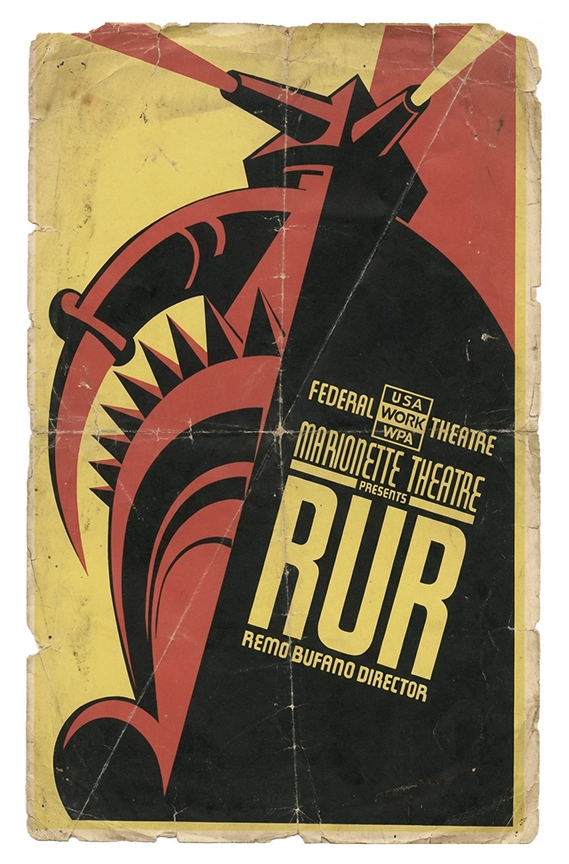

The word “robot” comes from the Czech word robota, meaning “forced labour” or “drudgery,” derived from the Slavic root rab (slave). Czech writer Karel Čapek introduced it in his 1920 play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), though his brother, Josef Čapek, coined the specific word. He intended for these artificial workers to be seen as servants performing compulsory labour, much like serfs.

Karel Čapek

Robots eventually came to symbolise progress, for better or worse. They represented a progression from the known into the future—and thus, the unknown. In images of these futuristic machines from the 1950s, we see a standardisation of what these automata should look like: riveted bodies with stiff movement, reassuringly defeated by an inability to climb stairs, and easily defined by their containment in recognisable materials.

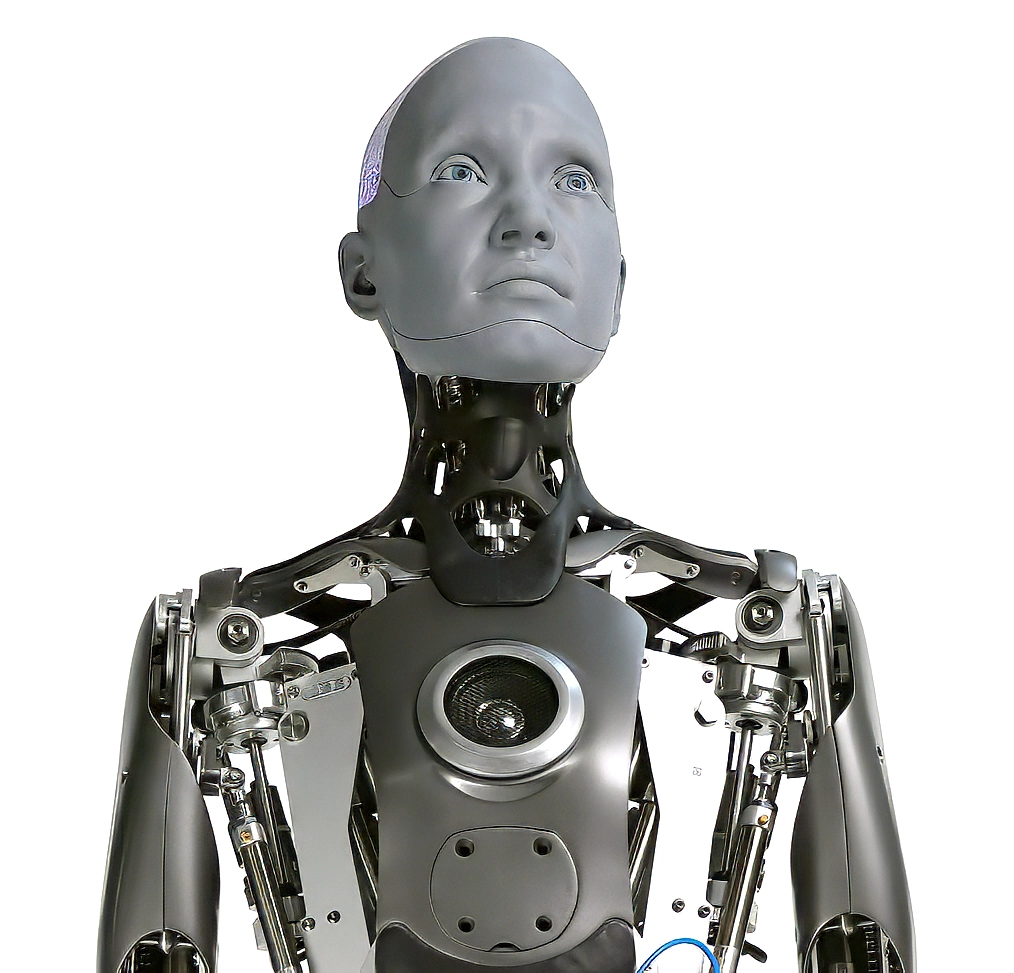

Recent representations of robotics have shifted toward a carbon copy of a human, pushing us into the Uncanny Valley. In this psychological state, humans see themselves duplicated in an eerie way. The Uncanny Valley is a region of negative emotional response towards robots that seem “almost” human. This new simulacrum, a copy, can often perform actions beyond human ability. However, the popular notion that robots never sleep is incorrect; for example, continuous, unsupervised learning can make neural networks unstable. They require updates and maintenance, they need ‘downtime’ just like the humans they are emulating

Modern mechanical robots still have servo motors whirring. As seen in Boston Dynamics and Tesla‘s androids, they jump, dance, and even make you a cup of coffee, yet they still possess that authentic robotic sound. Some reassuringly have parts of their human facade cut away to reveal the mechanics within.

Interestingly, the new robot AI has no real definable or recognisable features. When it is necessary to represent AI in an illustration, it is rendered either as an abstraction or, more commonly, the ubiquitous sparkle icon. Gone are the pneumatics, cogs, and glowing glass domes. Tech companies represent it as a magic trick, making it unnecessary to draw the components at all.

Now, it’s like trying to draw God.